Editor’s note: May 3 was the 150th anniversary of the consecration of the diocese’s first bishop, John McLean. There was a service at St. Alban’s Cathedral on that day to honour this anniversary, followed by a social afterward. This is the second article in a two-part series that looks at McLean’s service to the diocese.

PRINCE ALBERT — The College of Emmanuel and St. Chad continued to grow, with a classroom building opened formally by David Laird, the Lieutenant Governor of the North West Territories, in 1880, and a further dormitory building with classroom space constructed in 1881. The College’s first scholarship was also established, a gift from Lawrence Clarke. This occurred on the occasion of a visit from the Marquis of Lorne, Governor General of Canada, and was, by Royal consent, designated as the Princess Louise scholarship.

In January1882, at a public meeting in Prince Albert, resolutions were passed endorsing a proposal to take steps towards the establishment of a university, with Emmanuel as its core. That same year, a lecture room was built in the centre of the town of Prince Albert, three miles distant from the main college. This building would provide a classroom in which young men might study in order to qualify to enter university courses. The lecture room would also be used for Sunday services. (The site is currently the location of Bocian Jewellers and the Kirkby-Fourie Law Office.)

Then, in 1883, due in large measure to the personal lobbying of the bishop and his wife, Kathleen, an act was passed by the Government of Canada “to establish and incorporate the University of Saskatchewan and authorize the establishment of a college within the limits of the Diocese of Saskatchewan.” A farmer from Port Hope, Ontario, sponsored the petition in the House of Commons. This act gave the institution status to confer degrees in all faculties, but no religious tests or qualifications were to be required except for degrees in divinity.

It also established the Governor General as Visitor, and ruled that all statutes and regulations of the University must be laid before the Secretary of State for Canada, and secure the approval and signature of the Visitor. The bill was assented to by the Governor General on May 25th, 1883.

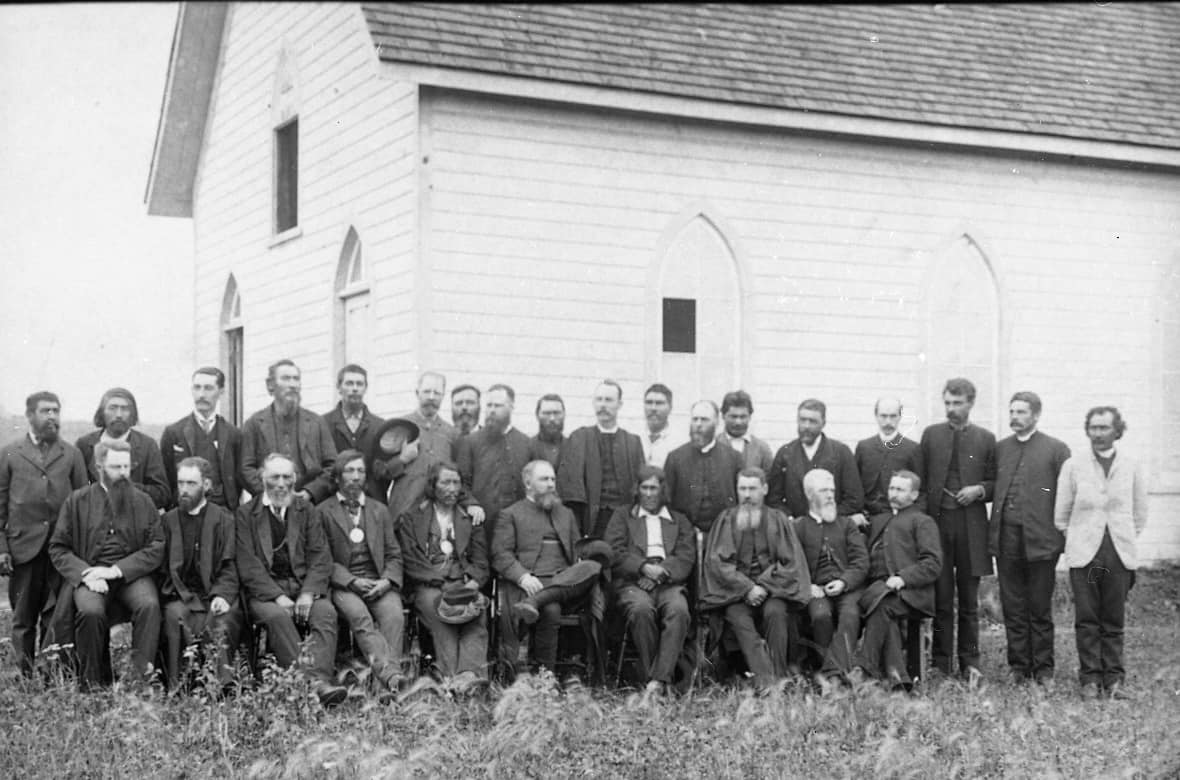

Although reduced in size in 1883 by the creation of the diocese of Qu’Appelle, McLean’s diocese had 22 clergy and seven catechists by 1886. This reduction, which strained his friendship with Machray, McLean accepted with reluctance.

The bishop was in the town of Prince Albert during the rebellion of 1885. No one who was in Prince Albert during those days of danger and anxiety will ever forget the bishop’s sermon on the Sunday after the Duck Lake fight. The North West Mounted Police and the local militia were drawn up in the square.

The bishop took his stand under the flagstaff in the centre, and, in words of patriotic eloquence, spoke of the noble citizens of Prince Albert who had fallen in the Duck Lake field of battle, of the glorious traditions of British law and justice, and of his faith in the permanent stability of the Canadian Dominion.

‘In the autumn after the resistance the Synod met. It was the bishop’s last Synod, and in his address, he said: ‘“Since we last met, I have been able to visit, and hold Confirmation, in every mission in the diocese but one, and this will be shortly visited. In the great majority of cases I have made at least two visits to each mission.”

As a parish priest, John McLean had been a great believer in good old-fashioned house-to-house pastoral visiting, not merely to talk about crops, financial prospects and other material subjects – all of which he willingly discussed – but in each household he would always read from Holy Scriptures and pray. Doing this, he believed was the best way to promote the spiritual life of the Parish. This practice he maintained during his episcopate. He often quoted the old saying that “a house-going parson makes a Church-going people.”

It was this commitment which led to Bishop McLean’s early death, as after the Synod was over, although he was not in good health, he started on a long visitation of the diocese. In his diary he writes as follows:

‘“Monday, August 16.– Left home with Hume.”

‘“Tuesday, 24th.– Reached Calgary.”

‘On the 29th he received a telegram telling of the birth of a son, but sent word that he must push on for Edmonton, as his work must not be neglected, but that he would return as soon as possible.

‘“Sunday, September 5.– Confirmation in All Saints’ Church, Edmonton.

‘“Monday, September 6.– I did not feel well to-day, but started on our return journey. On going down the hill near the fort we met a cart, and, there being no room to pass, our waggon was upset, and we were all thrown out. We, however, proceeded on our journey soon after; but I became seriously ill, and after proceeding five miles we returned to Edmonton, where I lay for three weeks at the Ross Hotel under medical charge. I became very ill and very weak; I sent back our team to Calgary on the second day. By the doctor’s advice I had a large skiff built by the Hudson Bay Company, with the stern part covered with canvas like a tent.

“Two men were engaged to conduct it to Prince Albert, a distance of six hundred miles by water. We reached Fort Pitt on Thursday, October 7, exactly eight days from Edmonton, which we left on September 29. Hume gave great help in working the skiff, and was most kind and attentive to me, both at the hotel and in the skiff. I continued very weak until we reached Fort Pitt. During the last two days I have been feeling much better, and am now writing up this note-book in the wood on the river bank, where we have taken refuge from a cold head-wind. Our progress is slow; we may have snow and ice in a day or two. I think of going overland from Battleford.”

The bishop was so ill when he reached Battleford that he was obliged to remain in the skiff, and his son, Hume, feared that he would not live until he reached Prince Albert. The weather was bitterly cold, ice having begun to form on the river; however, the men worked very hard, assisted by Hume, a lad of 15, who did all he could for his beloved father, whom he described as so sweet and patient in all his pain and weakness. He was constantly singing to himself during the weary hours of night.

This dear son, Hume Blake, died at Athabasca Landing, May 16, 1893, in his twenty-second year and is buried in the family plot at St. Mary’s.

After the bishop’s return home, where he finally saw his newborn son, Allan, he rallied considerably for a few days, but he was too much weakened by the hardships of the journey. Fever set in; he was delirious at times, but even in his wanderings his beloved diocese occupied his thoughts, and at times he imagined himself conducting meetings with his clergy.

On Saturday afternoon, November 6, he spoke in the most eloquent manner of the future of the diocese; then he kissed all his loved ones, and shook hands with others who were with him. As the sun was setting, he asked his daughter, Mrs. Flett, to help him to sit up, and had the blinds drawn up so that he could see the sunset; then he said:

‘“Do bring lights; it is growing very dark.”

‘From that time he spoke but little, but appeared to be in a sort of stupor, from which he was roused to take stimulants. About 5 a.m. on Sunday morning his wife was standing beside him, and he said to her: “My lips are getting so stiff;” and then he kissed her, with loving words of all they had been to each other. He did not speak coherently after that, but became unconscious, and remained so, surrounded by all his family, until 12 p.m., when he fell asleep like a little child.

He was buried in St Mary’s churchyard with all the pomp the Anglican Church and the town of Prince Albert could muster. The Prince Albert Times and Saskatchewan Review mourned him as the town’s best friend, “the central figure of our community,” and his old friend Machray praised his “great and varied gifts, readiness of utterance, and unceasing devotion.”

According to the reminiscences of the Reverend Canon J.F. Dyke Parker, Bishop McLean was the first official chaplain appointed to the North West Mounted Police; therefore, his funeral was conducted with full military honours. Although a very cold day, it was estimated that over 1×200 attended to pay their respects.

In Prince Albert McLean had been perhaps the leading figure, as the local newspaper and the journal of the HBC post show. The activities of his large family were followed with a similar interest, not unsurprising in an isolated community. Three of the five daughters were married in Prince Albert in the 1880s to clergymen (Jessica to the Reverend Ronald Hilton in 1886, Frances to the Reverend James Flett in January 1882, and Wilhelmina to the Reverend George McKay in October 1882), and the family was still in residence there in the 1890s.

In fact, after Bishop McLean’s death, a house was built in which Mrs. McLean could reside as the bishop’s residence was then required for Bishop Pinkham, who succeeded Bishop McLean. That house was subsequently moved into the City of Prince Albert in 1927 or 1928 and is still standing in the 700 block of 15th Street West.

McLean seems to have had good relations with his laymen, but could be critical of clerical brethren such as the learned but eccentric Newton or the Reverend George McKay who, busy ministering from Fort Macleod (Alta) to Indians, mounted police, and ranchers, failed to keep in touch with his bishop. The church at large recognized McLean through honorary degrees in 1871 from Kenyon College, Ohio; Bishop’s College, Lennoxville, Que.; and Trinity College, Toronto, and in 1881 from St John’s College, these having, it is worth noting, high church leanings.

Despite his difficulties, McLean’s accomplishments were substantial. He made valiant efforts to secure Anglican missionaries for the settlers attracted by the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, but his headquarters in Prince Albert was remote from the railway route chosen and he was preoccupied with the established work among the First Nations and mixed-bloods. This work was not made easier by the strains that led to the North-West resistance of 1885.

Nevertheless, by the time of his death he had taken important steps towards the training of a native clergy, he had consolidated Anglican missionary work among the northern Cree, and had initiated it among the Blackfoot, Bloods, Piegans, and Sarcee of southern Alberta. McLean attributed to the work of the missionaries the comparative quietness, during the rising, among the First Nations and mixed-bloods under Anglican influence.

As we have seen, Bishop McLean was very successful in his attempts to raise funds for the Church. He was described as “a very clear, lucid and forceful speaker.” Upon his death, he left the Diocese with funds exceeding $84,000.00 (more than $2,700,000 in today’s money) excluding the Emmanuel College scholarship funds. Given McLean’s expertise, the Archbishop of Canterbury, when introducing him, would refer to McLean as the Bishop of Catch-what-you-can (as opposed to Saskatchewan).

Old timers who attended services at St. Mary’s church would speak of the bishop’s sermons as being clear and cohesive. None of those individuals complained of their length, although even his Evening Prayer sermons were often 45 minutes in length. Archbishop Samuel Pritchard Matheson, who studied under McLean at St. John’s College, referred to what McLean had taught him with respect to preaching.

According to the Archbishop, McLean “committed all his own sermons to memory and delivered them verbatim.” Matheson told of following the manuscript of one of McLean’s sermons, preached at St. John’s Cathedral in Winnipeg, where Matheson followed the manuscript and found that the sermon was delivered “word for word – a remarkable feat of memory.”

Bishop McLean also exhibited a quiet, but very powerful sense of humour. In addressing missionary meetings after assuming his episcopate, he would sometimes tell his audience that he “travelled all the way on his snowshoes.” This was true, but only in a literal sense. The bishop was sitting on them, tucked away under him in the bottom of his dog-sled, just in case they would be needed. He also, when requesting Archbishop Machray for additional resources, made mention of Paul’s letter to Timothy.

Aside from a lay missionary at Sandy Lake, and a priest at Stanley Mission, the only support which he could claim was a deacon, Luke Caldwell, at Fort a la Corne. The verse from Timothy: “Only Luke is with me.”

In 1955, as part of the celebrations for the 50th anniversary of the Province of Saskatchewan, islands in Black Bay (location: 108degrees.57West on latitude 59degrees.29North) were named McLean Islands in honour of Bishop John McLean.